Thread warning. Lots of ideas, sort of loosely in response to @storminnmormon and about 3D printing and formative manufacturing. And especially drawbacks for 3D printing in terms of making rocket bodies in particular. 0/19 https://twitter.com/storminnmormon/status/1332468882909630469

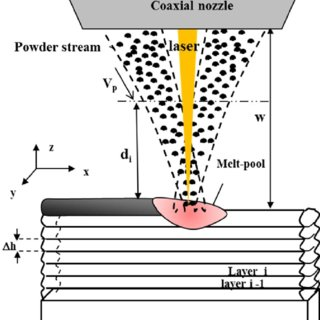

1) You actually have to optimize the materials *for* 3D printing. 3D printing will actually change the composition of your feedstock slightly. The alloy you put in is not the alloy of your part, especially for lightweight alloys, as some of the metal can actually evaporate.

2) Additionally, the huge thermal gradients and constraints of melting mean you have to optimize for thermal stress behavior and flowability. Melting point may also be a limitation.

3) In Directed energy deposition (the kind used for rocket bodies), there's both a powder-fed process and a wire-fed process. Powder tends to enable finer resolution, wire does lower resolution but higher throughput.

4) Powder deposition I think also has lower efficiency of material usage. Not all the blown powder ends up in the melt pool. But more importantly...

5) From what I understand, Powder tends to be a LOT more expensive as a feedstock than wire. Making powder is energy-intensive, and usually you have to sieve the powder so you get exactly the right powder distribution, so you often end up with a lot of waste in powder production.

6) Powder is also really slow. Both wire and powder have a pretty strong trade-off on throughput vs resolution. "complexity is free in 3D printing" is even more of a lie with DED than it is in other 3d printing processes. It can take weeks or even months to complete a part.

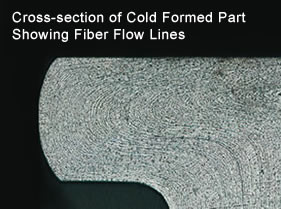

7) Defects and grainflow. Lets start with defects. Defects are tough to deal with as printing isn't typically done under high pressures and shears that are normally used to squeeze out defects in forging....

8) There are post-processing and in situ methods to deal with defects, using Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) or possibly bead-blasting or other tricks. This stuff can be done in situ to some extent, but it's more waste and more complexity and cost.

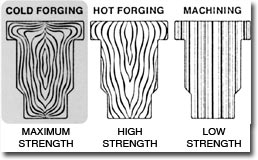

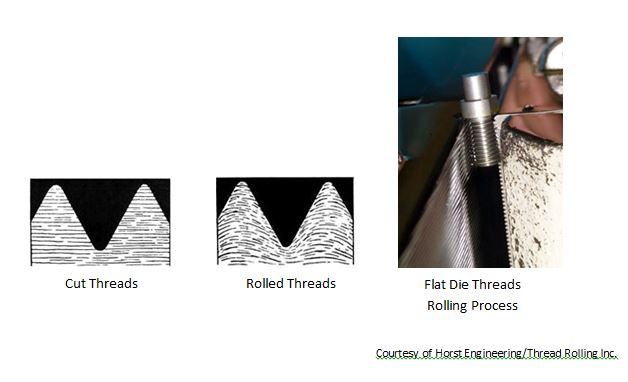

9) Grain flow is also very important & usually ignored for 3D printing. Metal is often treated like an isotropic material, but in fact, grain flow can impact strength by a factor of 2 or so, & it plays a big role in how failure occurs.

10) The highest strength to weight metal parts must optimize grain flow. In additive, basically impossible. In forging, flow-forming, or spin-forming, it's a normal part of the process. It's a MASSIVE advantage over 3D printing...

11) Formative manufacturing like forging, stamping, and casting also has massive throughput advantages.

Forging can give you hi throughput, surface finish, hi net-shape accuracy, & grain flow. Think of how awesome bolts & screws are. Cheap AND hi strength to weight AND precise!

Forging can give you hi throughput, surface finish, hi net-shape accuracy, & grain flow. Think of how awesome bolts & screws are. Cheap AND hi strength to weight AND precise!

12) It's possible to use digitally-defined formative manufacturing techniques. For instance, spin-/flow-forming or even digitally-reconfigurable tooling. This can allow you to get the surface finish, grain flow, low material cost of formative while remaining reconfigurable.

13) In summary, metal 3D printing won't give you the highest possible strength to weight ratio, it struggles with thin gauge material (sometimes essentially impossible), and often has low throughput and high material cost. Doesn't mean there aren't niches it can't work well in.

14) But, as someone who really learned engineering and materials science in the context of 3D printing before learning more about traditional techniques and formative manufacturing, I'm just continually impressed with stamping, forging, and casting. They are phenomenal.

15) Also: Process of forming sheet stock &forging & stamping under great pressure tends to cause sheer in defects, cold-welding the defects shut or at least converting them from stress concentrations into long, thin defects along load lines that cause little/no strength reduction

16) This is why forged weapons or other implements from pre-modern times often worked relatively well in spite of the low quality of the starting material compared to modern alloys. It also tends to slow the effects of corrosion.

17) A lot of times metal 3D printing is compared to casting parts, as often only castings can feasibly make the complex geometries. But even casting quality has improved a lot as modeling of the casting process has improved. Casting/injection-molding has WAY higher throughput.

18) You still usually need post-machining even for high quality 3d printing techniques. Anything with metal sliding on metal pretty much requires machining. Machining will always have a massive precision edge on additive. So you'll never get away from using multiple processes.

19) I love 3D printing & think it has a bunch of cool niches it works well for. Small regeneratively cooled rocket engines are one such niche. & often, the manufacturing process is just 1 choice among many. Multiple things can work. Execution matters more than anything else. /end

20/19 I forgot to mention something very pertinent to rocket bodies! The feature width of powder DED (the slowest, with the most expensive type of DED) is typically just 1.2mm or so, and the smaller, the slower.

21/19 If you think about it, the height of each layer must be no greater than the melt pool diameter. In fact, usually the layer height is much less than the minimum horizontal feature size. That means that the thinner the feature, the longer it takes to deposit material.

22/19 That makes it a bad choice for really thin-walled pump-fed rocket stages. For instance, Atlas's Centaur upper stage has really good mass fraction for a hydrolox stage. It is 3m in diameter, 10m long, but the stainless steel wall is just 0.5mm!

23/19 Wire-fed DED usually has minimum feature size of at least 10 times that (5-10mm). powder-based is almost there (1.2mm for off the shelf machines), but you should know that as you approach the minimum feature size, the quality tends to reduce.

24/19 Plus, as you reduce feature size, throughput reduces proportion to the inverse squared or worse. Half the feature size means at best a quarter of the throughput. That means it could take literally months or even years to get a large stage done if the wall thickness is small

25/19 Plus, for for large, thin-walled things like a Centaur tank, the material wouldn't be stiff enough to hold itself up and keep tolerances.

26/19 And a MAJOR, MAJOR problem with trying to print thin-walled tanks is the risk of pin-hole leaks. MUCH less of a problem with fabbing it out of quality sheet metal.

27/19 All these things push you away from thin-walled stainless. I'm sure they're using aluminum to gain a little relief. But it's likely still a lot thicker than it could be, just due to this minimum practical gauge issue.

28/19 It may be less of a problem for a pressure-fed rocket. Since you need thick walls anyway, not a huge deal. BUT again, you're losing massive structural performance. You're wasting some of the advantage of being pumpfed if you 3D print the tanks & have to use thick walls.

29/19 Being pressure-fed probably means using at least 3 stages. It probably means the most attractive types of reusability are off the table. You fundamentally have to use a bigger rocket for the same payload, which compounds your manufacturing cost problems.

30/19 Okay, I think I'm done LOL...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter